Treatment with the targeted drug gilteritinib (Xospata) can improve survival compared with chemotherapy for some people with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), new results from a large clinical trial show.

Treatment with the targeted drug gilteritinib (Xospata) can improve survival compared with chemotherapy for some people with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), new results from a large clinical trial show.

All participants enrolled in the trial had AML with specific mutations in the FLT3 gene that had come back after prior treatment (relapsed) or had not responded to treatment (refractory disease). Gilteritinib treatment increased median overall survival by close to 4 months compared with standard chemotherapy. Participants who received gilteritinib also had higher rates of complete remission and fewer serious side effects than those who received chemotherapy.

The findings were published October 31 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In November 2018, the Food and Drug Association (FDA) approved gilteritinib to treat adults with FLT3-mutated relapsed or refractory AML, based on interim results of the response rate from this trial. At that time, FDA also approved a companion diagnostic test to detect FLT3-activating mutations.

The new trial results “convincingly show that this is the way forward, this is the way we should be treating patients with this type of AML,” said the trial’s lead investigator Alexander Perl, M.D., of the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Relapsed/refractory AML is a really terrible disease, and this is a clear finding of improved survival in those treated with a targeted therapy versus conventional chemotherapy,” said Christopher Hourigan, M.D., D.Phil. , chief of the Laboratory of Myeloid Malignancies at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. “It’s a clear, incremental advance in the standard of care.”

Targeting FLT3 Improves Survival

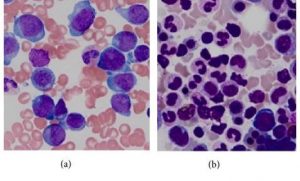

People who have AML with certain FLT3 mutations often have aggressive disease and poor overall survival, Dr. Perl explained.

These mutations in the FLT3 gene cause the FLT3 protein to always be active in leukemia cells, which can fuel their proliferation and survival. This is why researchers have considered FLT3 to be a good target for cancer treatment.

Gilteritinib, a type of targeted cancer therapy called a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, kills leukemia cells by binding to the mutant FLT3 protein and blocking its activity.

Other FLT3 inhibitors are being tested or are approved for treatment of AML. In 2017, the FDA approved midostaurin (Rydapt) for adults receiving chemotherapy for newly diagnosed AML with FLT3 mutations.

However, for relapsed and refractory AML, “gilteritinib has been the most successful in the clinic in terms of its response rate as a single agent, its tolerability, the duration of response, and its ability to avoid some of the common resistance mechanisms to FLT3 inhibitors,” Dr. Perl said.

The 371 participants in the trial, called ADMIRAL, were randomly assigned to receive gilteritinib or standard chemotherapy.

Not only did patients who received gilteritinib live longer than those who received chemotherapy (median overall survival of 9.3 months versus 5.6 months), they were also more likely to achieve a complete remission with full or partial return of their white blood cell counts to normal levels (34% of the patients who received gilteritinib versus 15% of those who received chemotherapy).

The most common severe side effects for those in the gilteritinib group were fever with reduction of certain white blood cells, anemia, and low platelet count. Approximately 11% of patients taking gilteritinib stopped taking it because of side effects.

Gilteritinib is also given in pill form, Dr. Perl said, which makes it easier and more convenient to take than chemotherapy.

Further Studies Needed to Continue Progress

The trial results are “not the final word on how to treat relapsed or refractory AML,” Dr. Perl said. Despite the improvement in survival, he stressed, long-term survival in this study was still low in both treatment groups.

“We are certainly making strides, but we really have a long way to go to improve outcomes for patients with relapsed or refractory AML that has FLT3 mutations,” he said.

Ongoing studies are giving gilteritinib earlier in the disease course and in combination with other therapies, as well as investigating why some patients with FLT3 mutations either don’t respond or develop resistance to gilteritinib.

In addition, clinical trials are comparing gilteritinib with other FLT3 inhibitors. In one clinical trial, for example, patients with untreated FLT3-mutant AML will receive either gilteritinib or midostaurin in combination with chemotherapy.

Researchers are also testing gilteritinib as a maintenance therapy for patients with FLT3-mutated AML who are in remission after initial treatment with chemotherapy or after a stem cell transplant.

“Gilteritinib is a good backbone to build on,” Dr. Perl said, “but, alone, it isn’t the final answer.”

Dr. Hourigan agreed. He also noted the poor long-term survival of patients in the trial and stressed that more progress needs to be made.

“We need to be smart about how we combine gilteritinib with other molecularly targeted drugs, how we time it with chemotherapy and transplantation, and how we continue building on this finding,” he said. “It’s great that gilteritinib can improve survival of patients compared with conventional therapy—that is the hope of precision medicine. We would like that survival to be much longer.”

Source: National Cancer Institute

Categories: NEWS